Art, Vision, and Surrender: A Conversation with Sarah Lewis, Pioneering Author, Scholar, and Founder

Sarah Lewis. Photograph by Simon Luethi, 2024.

Sarah Lewis (b. 1979) is a force of nature. She is a pathbreaking art historian, curator, author, founder, and professor at Harvard University. She published her first book, the bestseller The Rise: Creativity, the Gift of Failure, and the Search for Mastery (Simon & Schuster; now translated into seven languages), while she was an art history graduate student at Yale University. Soon after, she launched the extraordinary initiative, Vision & Justice, which is now a go-to cultural hub that features a book series, wide-ranging creative convenings, and other remarkable interventions. (See a beautiful recent New York Times write-up on this work.) She has received numerous awards for her work in all of these realms.

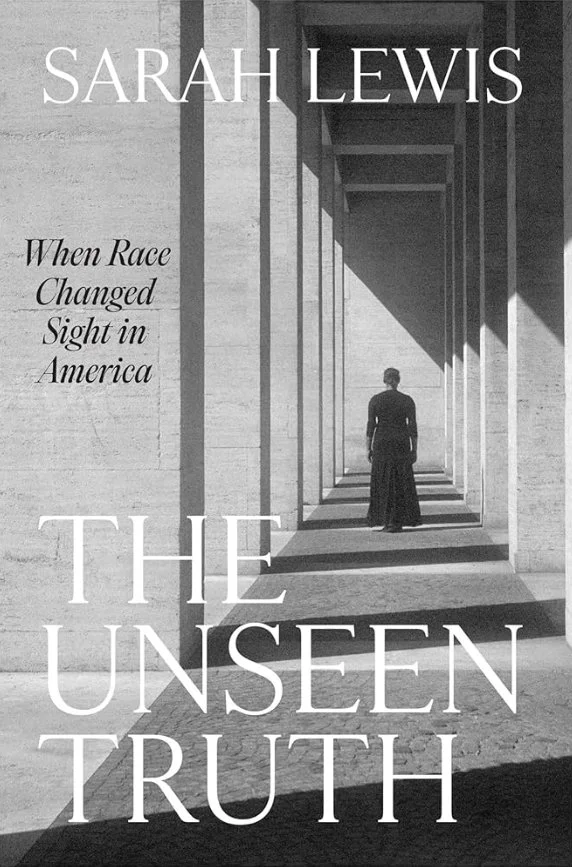

Lewis has just published a tour de force, The Unseen Truth: When Race Changed Sight in America, with Harvard University Press. She devoted around a decade to this book. It teems with hitherto unrevealed aspects of our collective histories. Information on the book tour is here.

Lewis and I recently connected for a conversation about her new book, as well as the relationships among her intuition, spirituality, and creative processes. She shared some of the incredible things that have happened along her journeys in writing and life, including the gift of a near-death experience and the enduring power of surrender.

Lauren Coyle Rosen: Could you share some of the arc of your creative process for your latest work?

Sarah Lewis: This latest book, The Unseen Truth, is one born of rigor and research, but also the kind of knowing that, at times, surpasses knowledge – the intuition, we often call it. And so, it’s a book that looks at how race changed how we see. The case study is the completely, effectively, unknown Caucasian War (1817—May 21, 1864), which showed Americans that there's a fiction at the basis of the entire regime of racial domination, racial hierarchy – that fiction being, that there's really any fact on which to rest the idea of racial whiteness and, therefore, any fact upon which to rest the idea of white racial supremacy. And that moment was startling in mid-nineteenth century for Americans. You see it in the work and the performances, photographs, and writings of a range of figures – some of the most well-known in American life, from Mathew Brady (ca. 1822-1824—1896) to P.T. Barnum (1810—1891) and Frederick Douglass (ca. 1818—1895). Then, in the twentieth century – and even earlier – all the way up to Woodrow Wilson (1856—1924), when he’s president.

The process of writing the book, I think, forced me to call upon the full range of resources we have as individuals, especially when we're tapped in. I think what readers might find most curious about the book is the density of the footnotes. It has over a hundred pages of footnotes. I felt really called to go to so many different sites, and needed to go to so many different sites, whether it was archives or of the kind that I'm not familiar with – archives of maps, for example – or repositories that contain important material. An instinct told me that something might be there. And then, the trip to the Caucasus region itself, which was, in effect, born of the kind of coincidences that are never coincidences. I’ve been really grateful for the intuition and guidance that I received in the process of writing the book.

Lauren: That's amazing. I'm just remembering something that you shared on social media about your ancestors guiding you to a documentary archive. Is there anything you’d like to share about that?

Sarah: Yes, there was. One of the major figures in the book in chapter five has his papers in an archive of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University. And the fact that this individual made it in the book was really, truly a function of a kind of divine intervention. It's the only way to put it. I've heard of him as an art historian. He's someone whom we've written about; people have written about Freeman. Well, there are two really. Freeman Henry Morris Murray (1859—1950) was one of the few Black clerks in Woodrow Wilson's administration, working in the early twentieth century. He's the first art historian to write in his nonexistent free time. He spent evenings writing the first book about race and representation in the United States, about public monuments and sculpture, in 1916. I had a sense that there was more to his story. And there was. I went to the papers, his archives at Howard, and pored over them.

A few days later, I had this extraordinary event happen that let me know, somehow, how important that research was. I was fashioning the final chapter about his work with Wilson and that of another Black clerk whose archives are in the Library of Congress. Now, mind you, I hadn't called the Howard Archives. As a scholar, you don't really call archives that much. You typically now email them and set up appointments. For some reason, that next week, I can't – no one can figure it out. My cell phone voicemail began call forwarding; it was somehow linked to the voicemail of the head archivist at Howard. So, when you would call, it would forward all my calls to the Howard Archive. My mother called, and she said, I just left a message for you in the voicemail of the Howard archivist. Then, with my best friend from college, my roommate, it was the same thing. Then, the sweet archivist called me, and then wrote me an email saying, “I'm not sure what's happening here, but your mother…” [laughs]

Lauren: All roads lead to the archivist. Reroute. [laughs]

Sarah: Yes. So, then, I called Verizon, asking, “Why are my calls going to the archivist?” They didn’t know. No one could figure it out. And then, it just stopped. It stopped when I figured out why I needed to see those papers, and the importance of Freeman Henry Morris Murray for the book. Wow. Now, if that's not an act of, I mean, a spiritual intervention, a kind of direction clarity, I don't know what it is. [laughs]. It literally prevented me from communicating until I figured out what it was in the archive. So, I had many moments like that in writing this book.

Lauren: That is so great. Would you get dreams or mind's eye visions about that part of the book, or about other parts or books, that were crystal clear or that were coming to you?

Sarah: Yeah, I mean, all along – I think in writing The Rise, and other publications since then; I've written at least 30 essays, articles, and book chapters since then, and Vision & Justice, the volume. I feel as if they've all been assignments. I don't know about dreams, but I do think that we receive impulses at all times. And I try my best to be attentive.

I think the most important event, though, was the miracle of the car collision I was in about four years ago now. That event was profound. I'm so grateful for it. There, it was made clear to me through what I saw in that near-death experience that the writing and the current projects – what I'm putting into the world now – was what I was meant to give and why I'm here.

Part of why I think this series is vital is because we often don't speak about the creative process. We should speak more honestly about the creative process. And I mean, full stop. When I wrote The Rise, I conducted a research experiment that sort of surprised me. I read every Paris Review interview, with writers from every decade, that were published. And the theme is, you see, the consistency of a kind of knowing that there is an act of co-creation, regardless of what you believe or don't believe – that there is something that is pouring through you. You're not just doing it, but, in effect, we become an instrument of a kind. It was so consistent across the vast array of artists and writers that you start to realize how much we're robbed of by being shy at times, when it comes to speaking about what really inspired you, what really made you get to the archive. And I think, for me, after the collision, the miracle, I lost a lot of fear about speaking frankly about these things and embracing it.

Lauren: Before, were you worried that people would judge it in a certain way, or maybe attach certain preconceptions to it?

Sarah: I don't think that I was worried so much as – well, I think we're all conditioned to keep the creative process that we all experience somehow private. I wasn't consciously afraid. I mean, I wrote a whole book about it, right? The Rise, in thinking about failure, forced me to engage with the spiritual discussions about how we refashion and assemble our lives. And one of the main tactics of that is in a surrender. That chapter on surrender really forced me to talk with folks who would be vulnerable in that way. I remember a conversation I had with Ben Saunders (b. 1977), who is an Arctic [and Antarctic] explorer. There are a great, great talks out there that he has given – TED Talks, for example. He is now the third person in the world to ski solo to the North and South poles. His feats were so incomprehensible in terms of difficulty and duration, and with what he had to withstand, that I was really captivated by our conversation. He ultimately, after years of speaking to him, disclosed that it wasn't strength or endurance or his fitness that allowed him to achieve what he has, but instead a very spiritual act that he could only, in the end, describe as a surrender – not giving up, but giving over to something larger. And in his case, it was very vivid because he would have to do things like trudge on ice sheets that were constantly moving because of climate change and drag a sledge on his back with 200 pounds, contending with weather at sub-50-degree temperatures. He would sleep, and then, in the morning, check his GPS, and he would at times realize that his gains from the prior day were wiped out because of the ice loading in the opposite direction. So, how do you keep your mental acuity and a [physical] capacity, and how you remain encouraged? Well, for him, it was surrender in moments like that. So, there's a co-creation in that, too. There's no committee that's going to stop how that ice is flowing right now, at least on the planet. [laughs] We're trying [to address] climate change. There's no one to turn to. I have to give over control to something else and control what I can.

I think that’s what we do in the creative process. We control what we can. We sharpen our instruments. We study as much as we can. We become proficient. We learn the craft. We travel to the archives. Then, you have to kind of stand with your arms open to the universe. There’s a line that Mark Bradford (b. 1961), my friend, a painter artist, said that I love. I think it's what we all basically do. He finds weird discarded, found materials to create his abstract paintings. And he said, in the beginning of the process, “I often think to myself, ‘Well, what I have isn't here, so I need to start going walking to make myself available to the universe to find what I need.’” And that's what he does, and that's what we all do.

Lauren: That’s amazing. Do you have techniques that you use regularly for that process – I call it “getting out of my own way.” Sometimes, I find that I am getting in the way of my serving as that instrument, or of appropriately aligning to whatever force is there to co-create with me. You seem to me, from afar, to be this person who is just moving in flow state with such grace and wide impact, all the time. I wonder if you have advice for people on how to do that. [laughs]

Sarah: Aw, that’s so kind. I'm working on the processes and practices, and I think over the last, I want to say, nine months, I've found new ones. I think that the most important, though, is finding and staying in a state of joy regardless, in a way that’s not dependent on context or events. Just because. I think that’s critical for any flow state. You have to be able to seek that out, whether it's through gratitude, whether it's contentment. But then, we have to think about all the different ways that we are activated and animated, whether it's how our body is feeling that day, how we are, how we use the practice of meditation or not, how we sustain our focus, and what our filters are for letting distractions come in or not.

I try to stay cleaned out so that I'm available basically. Meditation really helps. I think also just checking in with my self-talk. Inner dialogue is key. Speaking to myself the way a best friend would. It is important because with those inner narratives, we become what we believe. We become what we say to ourselves. And often, it’s in those quiet moments, where we don't quite realize that we're not being our best friend, that we're doing the most damage. And it's invisible. It's quiet, silent, but there. It's there. Working on that has been really important. And I do all the other things. I try. But most of all, just being kind to others and to myself. Being soft with myself has allowed me to remain strong.

Lauren: That’s beautiful, because these things are often seen as mutually exclusive, but as you so well say, they're not at all. I believe that fully. I was wondering, too, about how you said that often in our quiet states, we realize that we're not perhaps being our own best friend. That brought up for me the inner critic that often lives in my head, at least – and I think lives in a lot of our heads. Or this inner censor. And it’s so subtle. It often operates at this low hum beneath the level of consciousness. And with your work on visual culture, it is so tremendous how you show the ways that visuals are constantly imprinting, for example, our subconscious levels in ways that we don’t usually recognize, but in ways that fundamentally shape our experiences and understandings of ourselves and the world.

Sarah: Yes, I do think that what connects all of my work is pointing out or analyzing – offering clarity about, I hope – what we're failing to see, ultimately, and what narratives are contained therein, what the narratives mean. What we're often failing to see is the importance of culture, for example – for the narratives about belonging and who counts in society. That is the kind of societal self-talk – to connect it to the previous conversation, in a way – in The Unseen Truth. It's looking at how the system of racial domination was maintained through the signs and symbols of culture that were meant to support the regime despite the fiction of it all. With Vision & Justice, we're there, I think, able to understand the importance of visual culture – pictures, public monuments – as integral, as much as laws and norms, for liberation in the context of citizenship and patriotism and nation and race.

Cover of Sarah Lewis' new book, The Unseen Truth: When Race Changed Sight in America. Harvard University Press, 2024. Out now.