Art in Illusion: A Conversation with Iconic Photographer and Artist Lynn Goldsmith

Portrait of Lynn Goldsmith. Image courtesy of Lynn Goldsmith.

For legendary celebrity photographer and artist Lynn Goldsmith (b. 1948), her creations are all about navigating the illusion that is the world of forms and tapping into connections that run throughout it. Founder of the first celebrity portrait agency in 1976, she has generated some of the most well-known portraits of artists and figures as diverse as David Bowie, Miles Davis, John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Madonna, Ram Daas, Ani DiFranco, Joan Jett, Blondie, Bob Dylan, Muhammad Ali, Barbra Streisand, and Tom Waits. Goldsmith is also a remarkable visual artist who works in painting, mosaics, and other media. In the ‘80s, she performed as a musical artist under the name Will Powers. She has received numerous awards and has published around fifteen books. Recently, Goldsmith has been prominently featured in the news concerning her victory at the U.S. Supreme Court, where she successfully challenged the Andy Warhol Foundation so that she retained the exclusive copyright to license a striking 1981 portrait of the late artist Prince that Andy Warhol had altered with one of his signature portrait-rendition styles.

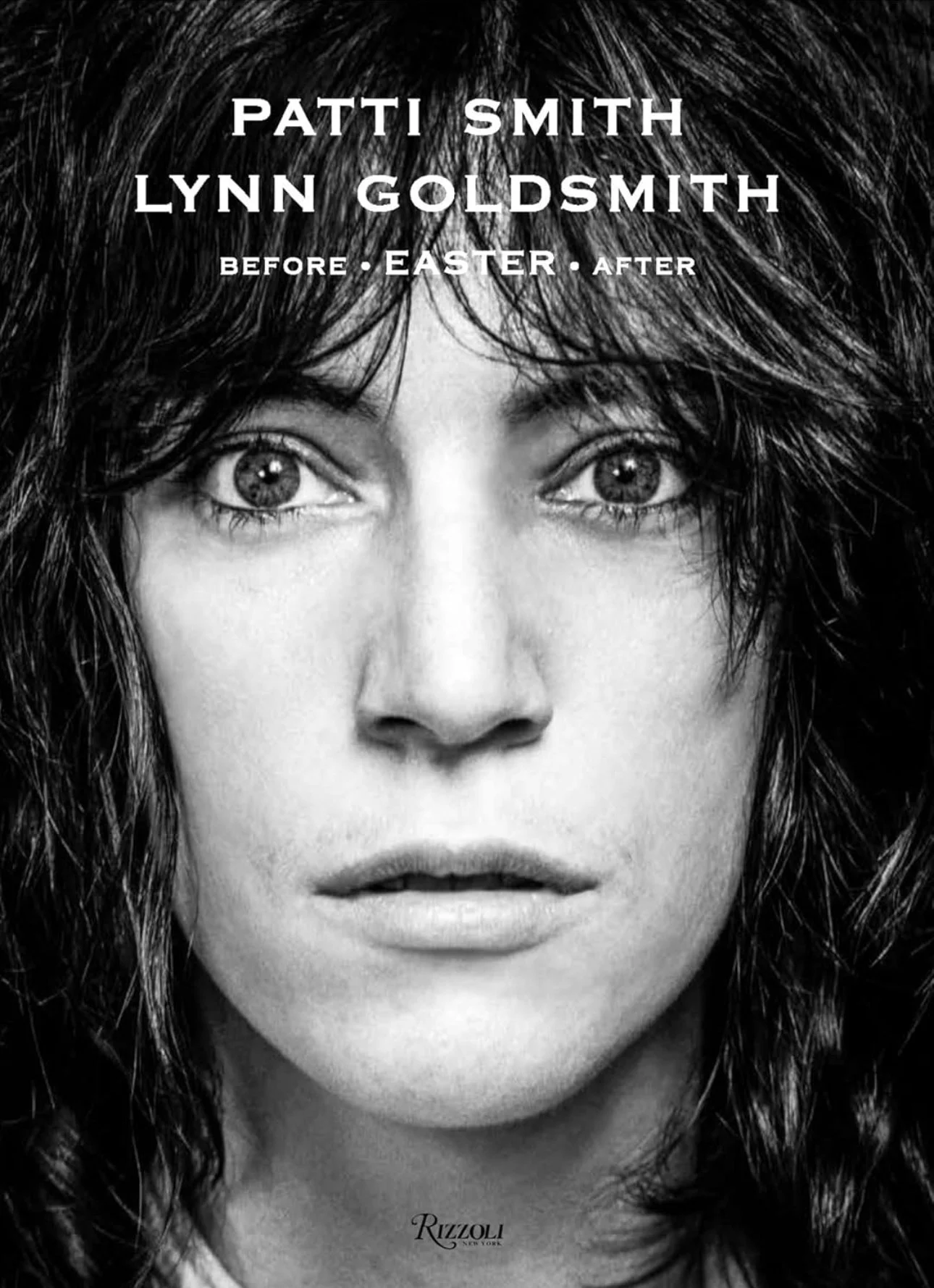

Goldsmith and I recently reconnected over a majestic, inspired book she coauthored with Patti Smith called Before Easter After (to be released in early October, with preorders available now). Goldsmith and Smith have been friends since they met in New York City the ‘70s and have collaborated intermittently since then. “We’re both worker bees,” Goldsmith said. “There are places where we can help each other in what we do and enjoy that collaboration.”

Book cover portrait of Patti Smith, by Lynn Goldsmith.

I spoke with Goldsmith about her work and journeys, as well as the roles of intuition in her art and life. She also shared some of the profound spiritual experiences she has had over the years, including temporarily leaving her body and becoming one with light – in a much sought-after state that is called samadhi in Hinduism, Buddhism, and related paths. Returning to the world of māyā, or illusion, was difficult. She had to reacclimate. These experiences altered her consciousness and recalibrated her relationships to her creative process and to pop culture, with its many idols.

Lauren Coyle Rosen: I would love to talk with you about any aspect of your spiritual or intuitive practices that relate to how you do your thing in the world, in any of your modalities.

Lynn Goldsmith: Well, I’ve always, fortunately, pretty much trusted my intuition. And that’s because it was proven accurate. That reinforcement allowed me to be able to continue trusting my gut and believing in a higher power. There are times where people question. I think this is because the result of trusting intuition may not be one that they consider to be successful.

My path, from as long as I can remember, has always been about learning and trying to not only be aware of other people and their takes on things, but to know that there was, more or less, a kind of ladder of enlightenment. And we're all on a journey to climb it. I remember, early on, talking to my mother about the Tower of Babel, when I was learning about it in school. I said, “Well, maybe the thing that separated the human beings who were building that tower to get to God…” — as far as I remember the story, it was that, when they got too high, God gave them different languages, and they couldn't understand each other. I remember saying to my mother, “Well, couldn't they have some singing?” Everybody understands singing, or that's what I naively thought. So, I've always been a searcher and felt that learning was, in great part, the purpose of being in one's body.

Lauren: So, there was no single moment where you had a radical awakening? It was more a lifelong continuum?

Lynn: Well, there are radical awakenings. You feel you have a radical awakening along the way, whether it comes from practicing a discipline like sitting in meditation or whether it comes from dropping LSD with the intention of learning, not with the intention of getting high – but with the thinking that a drug might open some pathway in your brain that will allow you to experience something that, otherwise, you don't know if you'll ever get to in this lifetime.

There were a lot of moments where I remember lessons being learned, but I've always felt that, in the rituals of every religion, there were positive things to be gotten to help me or any individual along their way in really being able to connect with the higher power.

I remember in college, in 1966 or 1967, I was a Rosicrucian, which meant that I had to learn astrology. And from there, it was the tarot. But before that, because of my Jewish background, it was the Kabbalah. I've always found that, whether it was Hinduism, which I'm very much drawn to due to the stories or myths that teach various lessons, or Buddhism, which was much drier – for me, anyway [laughs] – than being a practicing Hindu, and then there are different sects of that.

I've always been a searcher and felt that there were so many different religions to learn from. And there were things that disappointed me in those religions that would oftentimes be the prompt to then delve into a different religion. But that's the same thing that happens to me with nature. I also feel that there are many things to learn just from being present in environments where you have a sense of how they were here long before human beings. They might have been underwater, and now they're no longer underwater. Now, they're mountains that we can see and climb, but they're here. And our existence in our bodies is far more short-lived than what nature shows us as a deeper sense of time.

Lauren: I was just thinking, too, about your photographs and your visual art when you were saying that, because, for me, there's such a vitality or lifeforce in your pieces. This vitality, for me, is like a portal to a timeless realm, or perhaps it shows time as an illusion. Do you feel that way about your photography and other visual art?

Lynn: Well, I enjoy making visuals, and it allows me to express things that I, in all likelihood, don't really have all the words that can make me feel as complete as doing something that's visual. That's just my sort of way. I think we all have a kind of physical wiring, which allows us to express ourselves in a way that feels more complete to us. Take, for example, Patti Smith, who is also quite visually oriented. She draws. She paints. But really words are what, I think, get to the deepest parts of her. And for me, it’s not that way. And it's not because one is better, or one is worse. I think we just come into the world with a certain kind of wiring in our brains, with a history that allows us to experience the world very uniquely.

Lauren: Absolutely, I agree. Do you have strong internal visions in your mind's eye?

Lynn: I think so. [laughs]

Lauren: Do those inner visions relate at all to the work that you do in the external world? For example, do you see something in your mind’s eye that guides you before you paint?

Lynn: Well, sometimes. When it comes to photography, that's a different thing, because part of my reasoning for it is not the actual image that I'll make. It's more about the experience that I'll have, either meeting a certain person or going to a particular place. And the camera gives me purpose, and it allows me in, so to speak, faster than I think it would be for me without a camera. But it's not the image itself. It's the experience in making it that has the real value, especially in photography with portraiture. It's also true with my travels. For example, I went to India, or I've been to Russia, or wherever, and because of the camera, I can get into people's homes and be part of their life there. I have experiences that travelers aren't looking to have and don't have. But those are the experiences that I want to have. I want to know people, whether they're well known for something or whether they're considered, let's say, to be ordinary people, for lack of a better word, because I don't really believe that anybody is ordinary.

Lauren: Was it a calling for you, working with the camera? Did you feel like it was a vocation that came to you?

Lynn: No, no. And I still don't. [laughs] I use tools to make things, to get me where I want to go. Even when I was probably the most focused and spent the most time in meditation, I wanted to meet a variety of individuals who were, more or less, considered gurus. Some were considered avatars, people who have chosen to be here on the planet more to hold it together. And then, there are those who they instruct and send out into the world as teachers or gurus. And having a camera allowed me to meet certain people, to talk to them, to have an experience of them that I most certainly wouldn't have had if I wasn't making something, an image, that would be or could be useful to them. And that was also true of various writers who wrote about their own journeys – for example, Marianne Williamson, with her In Search of the Miraculous. I wanted to meet and know her. Or R.D. Lang, who wrote The Divided Self. So, a range of individuals that I probably would never have had a close experience with, and been able to kind of be taken along, if I didn't have a camera.

Sometimes, the camera is just a tool to make me feel comfortable in the world, or purposeful. [Today,] I rode my bike to Maroon Bells, which is sometimes considered to be the eighth wonder of the world. It's here outside of Aspen, Colorado, and it's about a ten-mile bike ride. When I get there, I take out my camera, and I make pictures, and then those pictures remind me of that particular bike ride. In some ways, I wish I could just have a paper and pencil and sit there and write something and have that, but it's visuals that make me feel more connected to myself and, therefore, to the world.

Lauren: With your portraits, are there any that come to mind that are particularly alive when you look at them again, where you almost feel that you can easily connect with their energy or their presence, maybe through the photo?

Lynn: Well, when it comes to celebrity portraiture, I'm part of what makes people feel connected to their “gods,” right? They have a picture of Bob Dylan, or they have a picture of Bruce Springsteen, or Patti Smith, or Richard Gere, or whoever it may be. They like to see various celebrities as icons. I don't really feel that way. I understand why. I feel more like I'm part of making the Golden Calf, and people need that because they need a manifestation. When I look at pictures, let’s say there are things – there was a fire ceremony that Ram Dass and a few other teachers had, and Elisabeth Kübler-Ross was there. The fire ceremony is where you write down various things that are concerning you, that are negative, and you throw them into the flame. And I have these photographs of Ram Dass and Elisabeth Kübler-Ross throwing their woes into the fire. It just reminds me very strongly of all the people who were there and the feeling that I had. So, those pictures are meaningful to me, I would assume, just in the way that pictures are meaningful to me, of me as a kid in our backyard blow-up swimming pool with my dad and my sister. It just brings back powerful moments of connection. Let’s say I have a picture of Bob Dylan that means so much to somebody. It's because they're connected to a moment in their life where some song that he wrote was the soundtrack for that moment, which is meaningful to them. So yeah, I think the human being, for the most part, needs visuals to help them feel – hopefully, to help them feel, period.

Lauren: Yes, agreed. Is there a sort of energetics of it that locks in for you in the creative process? I was just thinking of this line that I heard [photographer] Mick Rock say, in the documentary on his life: “Forget about your soul. I want your aura.” [laughs]

Lynn: Yeah, you have to get that connection so that it appears on the paper it's printed on. I try to make that connection all the time, or the visual isn't going to happen. But Mick, may he rest in peace, was an Englishman who always could come up with a way of saying things that were quotable. [laughs] I think that was more a quote for him, but in a couple of instances in my photographs, the aura of the person did appear, and that was really chilling and unexpected. And I certainly wasn’t trying to make it happen at all.

Lauren: Did you show the aura photographs to the people who were the subjects?

Lynn: Yeah.

Lauren: Did the subjects want those photographs with their auras published or used for anything?

Lynn: No, not that I know of. I know it happened to me twice [where the auras appeared in the photographs]. When that happens, it’s kind of like feeling it's got nothing to do with you. You just happen to be in a time and place, and it came out.

Well, it would be nice if you could do that [intentionally photograph auras], I think, a nice little trick. And people would definitely be attracted to any photographer or human being that could help them to see their own aura. I think that everybody's aura is there, and that's part of why some people's intuition about that person is clearer to them than it is to others, because their intuition is closer to being able to see or feel that aura.

Lauren: I'm so curious about your practice with samadhi. Did you cultivate it, or did it just come to you as a gift?

Lynn: Well, no, I had heard about it. When you're reading about gurus, when you meet teachers, along that path, especially in the Hindu tradition, you hear about what it is that samadhi has been for some people, but you don't necessarily think you're ever going to go there because it takes a lot of practice and discipline to be able to hold the kind of what's called Shakti to get there. And you can practice and practice and practice and never get there. And I don't think it's a goal. It's kind of like a place that's been described because those people who just wanted God so badly that they could – whether it's sit in meditation for well over 24 hours, or sleep on a bed of nails, or whatever – as yogi masters. It's something that happens, and it's really wonderful, but it, at least for me, is really quite scary because you leave your body. So, you do not know, necessarily, if you’re going to come back into your body. And if you're still on the path, if you've still got a lot to learn, you definitely want to come back into your body because that's how you learn. [laughs]

Lauren: Do you remember where you go when you leave your body? Can you recollect, once you've come back into your body, where you've been?

Lynn: Oh, yeah. But it's not like it's a place. It’s not like in a movie where it's all powder blue and clouds and pink cotton candy or anything like that. It's more like being in the light, being part of the light. You are gone. And you're part of the light. That's all I can really explain. And you are, in essence, no longer here.

Lauren: When you come back, do you feel like you're seeded with information from becoming one with the light, and then coming back into your body, into your appearance of a discrete being?

Lynn: Well, I can only speak for me. And for me, it was difficult and sad to be back in the world, and it took a lot of my energy to kind of acclimate again. I think it's a practice to be in the world, but not of it. And when you're not of it anymore, and you're not in it anymore, to come back is not like, “Oh, wow, I was just in samadhi.” No. It’s like, “Oh no, the world sucks.” [laughs]

It’s like people who die, their heart stops and yet medicine has come to a point where they can bring the person back. And they talk about having had an experience of leaving their bodies and then coming back into the world. So, things that I have heard about individuals who have been brought back medically are not unlike how I felt. There were many elements that were akin to that in terms of knowing that there's something else beyond your body, beyond what we know – or think of – as reality. It makes it much more of an experience that one can know that they had, where the world as it is, and was, is all illusion, is all māyā. But like anything else, it is hard to hold on to. And you’ve got to work for it.

About the Author

Lauren Coyle Rosen is the author of twelve books to date, four nonfiction and eight volumes of poetry. She recently completed a book coauthored with legendary singer-songwriter and feminist icon Ani DiFranco, and another with the great orchestral composer and jazz musician Hannibal Lokumbe. Both books travel the artists’ spiritual and creative journeys in their works and lives. Her debut album, Purify Flame, will be released on May 12, 2025. (Press release available here. Merch availablele here.) Coyle Rosen is currently a fellow at the Hutchins Center at Harvard University. She was a cultural anthropology professor at Princeton University, where she received the President’s Award in Distinguished Teaching. She has a law degree from Harvard Law School and a Ph.D. in Cultural Anthropology from the University of Chicago. More info can be found on her website, laurencoylerosen.com.